For over half a century, we’ve been told that saturated fat is the dietary villain responsible for heart disease. The roots of this widespread belief trace back to the mid-20th century, particularly to the work of Ancel Keys, a physiologist with a keen interest in diet and health. Keys’ diet-heart hypothesis, which suggested a direct link between saturated fat consumption, elevated cholesterol levels, and heart disease, quickly gained traction and profoundly influenced dietary guidelines worldwide.

But what if this narrative is not just wrong but fundamentally flawed?

Recent scientific investigations and historical analyses reveal a much more nuanced picture. The narrative that saturated fat is a primary cause of heart disease is crumbling under the weight of new evidence and re-evaluations of old data. Prominent studies and meta-analyses have begun to challenge the long-held beliefs, suggesting that saturated fats may not be the dietary villain they were once thought to be. Instead, the finger of blame might need to point elsewhere—towards processed foods, sugar, trans fats, and. polyunsaturated fats.

The story of how saturated fats were vilified is a fascinating one, involving a mix of early scientific enthusiasm, personal biases, and potential conflicts of interest. Understanding this history is crucial, not just for nutritional science but also for public health policies that continue to be influenced by outdated information.

The Birth of the Diet-Heart Hypothesis

The diet-heart hypothesis was first proposed in the 1950s by Ancel Keys, a physiologist at the University of Minnesota. Keys’ hypothesis suggested that dietary saturated fat raised cholesterol levels in the blood, which in turn led to heart disease. This idea was based on a combination of small human feeding experiments and some animal studies showing that high cholesterol could cause fatty deposits in arteries, which were thought to lead to heart attacks. For more on cholesterol, visit my article on eggs.

During his travels through post-war Europe, Keys observed that poorer populations in regions like Sardinia, Naples, and Spain, who consumed diets low in saturated fats, had lower rates of heart disease. This observation reinforced his belief in the diet-heart hypothesis. Keys was known for his persuasive and sometimes aggressive personality, which helped him promote his ideas effectively. He published no fewer than 20 papers in the late 1950s asserting his hypothesis.

One of Keys’ most significant allies was Paul Dudley White, nicknamed the “Father of American Cardiology”, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s personal physician. After Eisenhower suffered a heart attack in 1955, White publicly endorsed Keys’ hypothesis, bringing it into the national spotlight. The American Heart Association (AHA), under White’s influence, also began to adopt and promote the diet-heart hypothesis. This endorsement was a turning point, leading to widespread acceptance of the idea that saturated fat was a primary cause of heart disease.

One of Keys’ most significant allies was Paul Dudley White, nicknamed the “Father of American Cardiology”, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s personal physician. After Eisenhower suffered a heart attack in 1955, White publicly endorsed Keys’ hypothesis, bringing it into the national spotlight. The American Heart Association (AHA), under White’s influence, also began to adopt and promote the diet-heart hypothesis. This endorsement was a turning point, leading to widespread acceptance of the idea that saturated fat was a primary cause of heart disease.

The Seven Countries Study: Establishing a Foundation

One of the most influential pieces of research supporting the diet-heart hypothesis was the Seven Countries Study, led by Keys. Launched in 1957, this study was groundbreaking in its scope, involving 12,770 men in 16 locations across seven countries, including Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia, Finland, the Netherlands, the United States, and Japan. Keys believed that selecting these countries would help confirm his hypothesis.

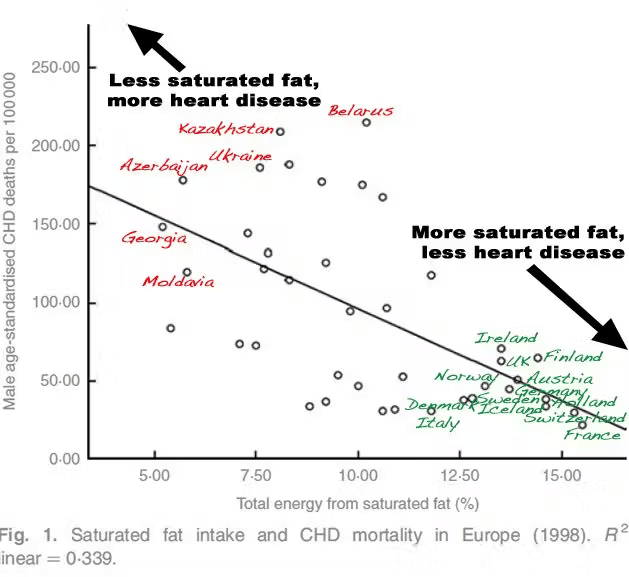

Indeed, the study found a strong correlation between saturated fat consumption and heart disease mortality. However, this study has been criticized for several reasons. Critics argue that Keys “cherry-picked” countries that would support his hypothesis while ignoring others, like France, Germany, and Switzerland, where high saturated fat consumption was not associated with high rates of heart disease. Additionally, the dietary data collected in the study was often incomplete or not standardized, and in some cases, like in Crete during Lent, the data did not accurately reflect usual dietary habits.

Despite these shortcomings, the Seven Countries Study became the cornerstone of the diet-heart hypothesis, influencing public health policies and dietary guidelines for decades.

The Influence of the American Heart Association

The AHA’s endorsement of the diet-heart hypothesis was significant. In 1961, the AHA officially recommended that all Americans reduce their intake of saturated fats and replace them with polyunsaturated fats from vegetable oils. This advice, heavily influenced by Keys, became one of the most influential nutrition policies ever published. It was subsequently adopted by the U.S. government and other health organizations worldwide, including the World Health Organization.

It’s important to note that the AHA had a significant conflict of interest. In 1948, the organization received a substantial donation from Procter & Gamble, the makers of Crisco oil, which contained polyunsaturated fats . This funding helped transform the AHA from a small organization into a national powerhouse, promoting the benefits of vegetable oils over saturated fats.

The Long Shadow of the Diet-Heart Hypothesis

As the diet-heart hypothesis gained traction, various large-scale, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted in the 1960s and 1970s to test the hypothesis rigorously. These trials, involving around 67,000 participants, aimed to establish a causal link between saturated fat intake and heart disease. Surprisingly, the results were largely disappointing for proponents of the hypothesis. While reducing saturated fat intake did lower cholesterol levels, it did not lead to the expected reductions in cardiovascular events or total mortality.

One of the largest and most significant trials was the Minnesota Coronary Survey, which involved over 9,000 participants and lasted for 4.5 years. Despite reducing participants’ saturated fat intake and lowering their cholesterol levels, the study found no significant difference in heart disease rates between the control group and the intervention group. These results were not published until 16 years later, likely due to the disappointing outcomes that contradicted the prevailing beliefs.

Another critical piece of evidence comes from the Framingham Heart Study, which began in 1948. Detailed dietary data collected from participants showed no significant relationship between saturated fat intake and heart disease. In fact, some data suggested that those who consumed more saturated fat had lower cholesterol levels and weighed less.

Modern Reevaluations and Emerging Consensus

In recent years, the diet-heart hypothesis has come under intense scrutiny. A growing body of evidence from new studies and re-analyses of old data suggests that saturated fats may not be as harmful as previously thought and are quite the opposite. For example, a comprehensive review published in the British Journal of Nutrition found no consistent evidence linking saturated fat intake with heart disease.

The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study, one of the largest epidemiological studies ever conducted, followed over 135,000 individuals from 18 countries. The study found that saturated fat intake was not associated with an increased risk of heart disease or mortality. In fact, higher saturated fat intake was associated with a lower risk of heart disease and stroke.

Paul Chek’s Perspective: A Holistic Approach

Paul Chek, a holistic health practitioner and author of “How to Eat, Move, & Be Healthy,” offers a different perspective on saturated fats and their role in health. Chek argues that not all fats are created equal and emphasizes the importance of consuming high-quality, organic, and unprocessed fats. According to Chek, many of the negative health effects attributed to saturated fats are actually due to the consumption of poor-quality fats from processed and industrial foods.

In his blog post “Saturated Fats, Diabetes and Carb/Sugar Consumption,” Chek responds to a common argument that dietary saturated fat is a significant inducer of insulin resistance, which is a major factor in diabetes. He counters this by pointing out that traditional diets high in saturated fats, such as those of the Inuit or the Maasai, do not show high incidences of diabetes or other chronic diseases. Chek emphasizes the importance of metabolic individuality, suggesting that people respond differently to various fats based on their unique biochemistry.

Chek also highlights the dangers of consuming trans fats and processed vegetable oils, which are often mistakenly lumped together with natural saturated fats. He argues that the repeated heating and processing of vegetable oils create harmful compounds that contribute to health problems, including insulin resistance and heart disease. Chek’s holistic approach stresses the importance of looking at the whole diet and lifestyle rather than isolating single nutrients as the cause of health issues.

Conflicts of Interest and the Role of Policy Makers

Despite the mounting evidence against the diet-heart hypothesis, dietary guidelines have been slow to change. One reason for this inertia is the potential conflicts of interest and longstanding biases within influential organizations and committees responsible for these guidelines. For instance, updated every five years, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) have historically relied on a limited set of studies and have not systematically reviewed the extensive body of evidence challenging the diet-heart hypothesis.

Emails obtained through the Freedom of Information Act revealed that members of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) acknowledged the lack of scientific justification for specific caps on saturated fat intake. Yet, these caps were included in the guidelines, influenced by longstanding biases and potential financial conflicts of interest within the committee.

The Path Forward

The journey to unravel the saturated fat myth is ongoing. While significant progress has been made in understanding the true impact of saturated fats on health, public health policies have yet to fully reflect this new knowledge. Policymakers must consider the latest scientific evidence and re-evaluate outdated guidelines that may no longer serve the best interests of public health.

In conclusion, the demonization of saturated fat appears to be based more on historical biases and flawed studies than on solid scientific evidence. As we move forward, it’s essential to adopt a more nuanced approach to dietary fats, recognizing the importance of whole, unprocessed foods and the complex interplay of various dietary components in promoting health. So, the next time you enjoy a pat of butter or a slice of cheese, remember that the science behind saturated fat is far more complex—and far less damning—than we’ve been led to believe.