When it comes to food safety, the United States often finds itself playing a bizarre game of catch-up. Case in point: the FDA’s recent decision to ban Red Dye No. 3 in foods and ingested drugs. Yes, the same dye that was declared a carcinogen and removed from cosmetics back in 1990. So why did it take over three decades for the FDA to take action on the food front? And what does this mean for other artificial dyes lurking in our snacks and drinks? Buckle up—we’re diving deep into the shady history of Red 3 and its colorful companions.

The Toxic History of Red 3

Red Dye No. 3, also known as erythrosine, was first approved for use in the United States in the early 1900s. Like many synthetic dyes, it is a petrochemical derivative—yes, a product of the same crude oil used to make gasoline and plastics. Petrochemicals are notorious for their toxicity, yet they have found their way into our food supply under the guise of adding color and appeal. The fact that we’ve been consuming substances derived from oil, something we put in our cars, should give us all pause.

By the 1980s, scientific studies began to uncover the dark side of Red 3. Research showed that high doses of this dye caused thyroid tumors in male rats. This led the FDA to ban Red 3 in cosmetics in 1990 under the Delaney Clause, a regulation stating that any additive shown to cause cancer in animals cannot be deemed safe for human consumption. However, the food industry’s powerful lobbying machine ensured that Red 3 remained in foods and medications, despite clear evidence of its dangers. For over 30 years, Americans have unknowingly consumed this carcinogenic compound in their snacks and sweets.

The irony reaches an almost comical level when you consider one of the most infamous places Red 3 is found: a popular liquid “nutritional supplement” often given to cancer patients in hospitals. That’s right—a drink meant to nourish those battling cancer contains a dye known to cause cancer. This beverage, which is promoted as a “lifeline” for patients struggling to eat solid food, is an emblem of a system gone awry. Instead of healing, it’s delivering more toxins to bodies already in a fragile state. It’s the perfect encapsulation of a broken system, where the goal of profit trumps the mission of healing. Hospitals—places meant to protect health—are serving carcinogens to those already fighting for their lives.

The problem is not unique to Red 3. Many synthetic dyes, including Red 40 and Yellow 5, have similarly dubious histories and yet continue to be used. The question remains: why are these dyes still permitted, and how many more decades will it take for regulators to act?

Where Red 3 Hides in Your Food

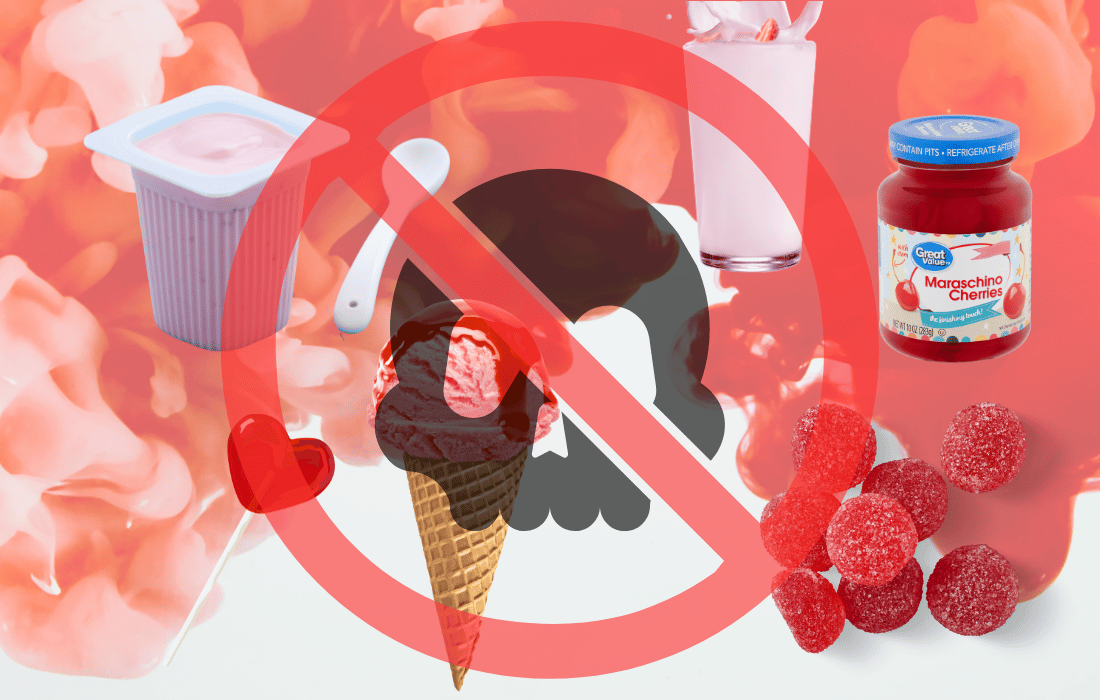

Red 3 is the culprit behind that eye-catching cherry-red hue in a wide variety of processed foods. Here are some common items where it’s found:

Candies: Think jellybeans, lollipops, gummies, and candy corn. Many brightly colored candies rely on Red 3 to achieve their vivid shades.

Baked goods: Snack cakes, pre-packaged cookies, and frosted donuts often use Red 3 to color glazes and fillings.

Fruit snacks: Popular children’s fruit-flavored snacks and gummy candies are frequently colored with Red 3.

Maraschino cherries: The iconic red cherry topping for cocktails and desserts owes its hue to this dye.

Gelatin desserts: Products like cherry-flavored gelatin often include Red 3.

Beverages: Some powdered drink mixes and fruit punches contain Red 3 to enhance their visual appeal.

Medications: Red 3 is used in certain chewable vitamins, cough syrups, and liquid medications to make them more palatable, particularly for children.

Liquid Nutritional Supplements: Used in hospitals, these recovery drinks—ironically targeted at improving health—are often dyed with Red 3.

The FDA’s recent ruling gives food manufacturers until January 15, 2027, to remove Red 3 from their products. Unfortunately, this means consumers will continue to be exposed to this carcinogen for years. The phased timeline reflects a familiar pattern of regulatory caution that prioritizes industry convenience over public health.

The Health Effects of Synthetic Dyes

Artificial food dyes are far from harmless. They are often made from petroleum byproducts and are linked to a range of health issues, particularly in children. Let’s dig deeper into the risks associated with these synthetic compounds:

Red Dye No. 3

Studies from the 1980s provided robust evidence that Red 3 causes thyroid cancer in lab rats. More recent research has pointed to its potential to disrupt thyroid function in humans, even at lower levels of exposure. The dye’s chemical structure is thought to interfere with the endocrine system, leading to imbalances that could have far-reaching effects on metabolism and overall health.

Red Dye No. 40

Red 40, another petroleum-derived dye, has been associated with behavioral issues in children, including hyperactivity and attention disorders. A 2007 study published in The Lancet confirmed a link between synthetic dyes and increased hyperactivity in children, even at low doses. Additional research has raised concerns about its ability to disrupt mitochondrial function and contribute to oxidative stress.

Yellow Dye No. 5 and No. 6

These dyes are common in chips, sodas, and baked goods. Yellow 5 has been linked to allergic reactions, including hives and asthma, while Yellow 6 has been implicated in adrenal tumors in animal studies. Research has raised concerns about their carcinogenic potential.

General Health Risks

Synthetic dyes contribute to oxidative stress, a key driver of chronic inflammation. Over time, this can lead to:

Metabolic disorders: Chronic inflammation disrupts insulin sensitivity, increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Neurological effects: Oxidative stress impacts brain function, potentially worsening conditions like ADHD and anxiety.

Endocrine disruption: Many dyes mimic estrogen, throwing hormonal systems out of balance.

Why the Ban Isn’t Enough

While the FDA’s decision to ban Red 3 is a step forward, it raises a larger question: why are we still allowing other toxic dyes in our food? The science on dyes like Red 40, Yellow 5, and Yellow 6 is equally damning, yet these additives remain legal.

The delayed action on Red 3 underscores a regulatory system that often bows to industry pressure. The food and beverage industry has spent decades lobbying against tighter restrictions, using misleading arguments about the safety and necessity of synthetic dyes. Meanwhile, countries in the European Union have banned or heavily restricted these dyes, opting for natural alternatives like beetroot and turmeric extracts.

RFK Jr. and the Make America Healthy Again movement have been vocal about the need to eliminate harmful additives across the board. Their advocacy highlights how regulatory agencies often prioritize corporate profits over public health. While the ban on Red 3 is a win, it’s far from the systemic overhaul needed to truly clean up the U.S. food supply.

What You Can Do

Consumers don’t have to wait for the FDA to act. Here’s how you can protect yourself and your family from synthetic dyes:

Read Labels: Avoid products listing Red 3, Red 40, Yellow 5, Yellow 6, or any “FD&C” dye.

Opt for Organic: Certified organic products are free from synthetic dyes and rely on natural colorants.

Just Eat Real Food (JERF): Fruits, vegetables, and animal products are naturally vibrant and free from harmful additives. Always try to source the highest quality you can (remember, pay the farmer now or pay the Pharma later).

DIY Snacks: Making treats at home lets you control the ingredients. Use natural dyes like beet juice, turmeric, or spirulina.

A Brighter (and Cleaner) Future

The FDA’s ban on Red 3 is a long-overdue step in the right direction, but it’s only the beginning. The continued use of synthetic dyes like Red 40 and Yellow 5 reflects a broken regulatory system that prioritizes industry interests over public health. By staying informed, making conscious choices, and supporting advocacy efforts, we can help build a future where our food is free from petrochemical-derived toxins. After all, shouldn’t the only oil in our lives be the kind we put in our cars?