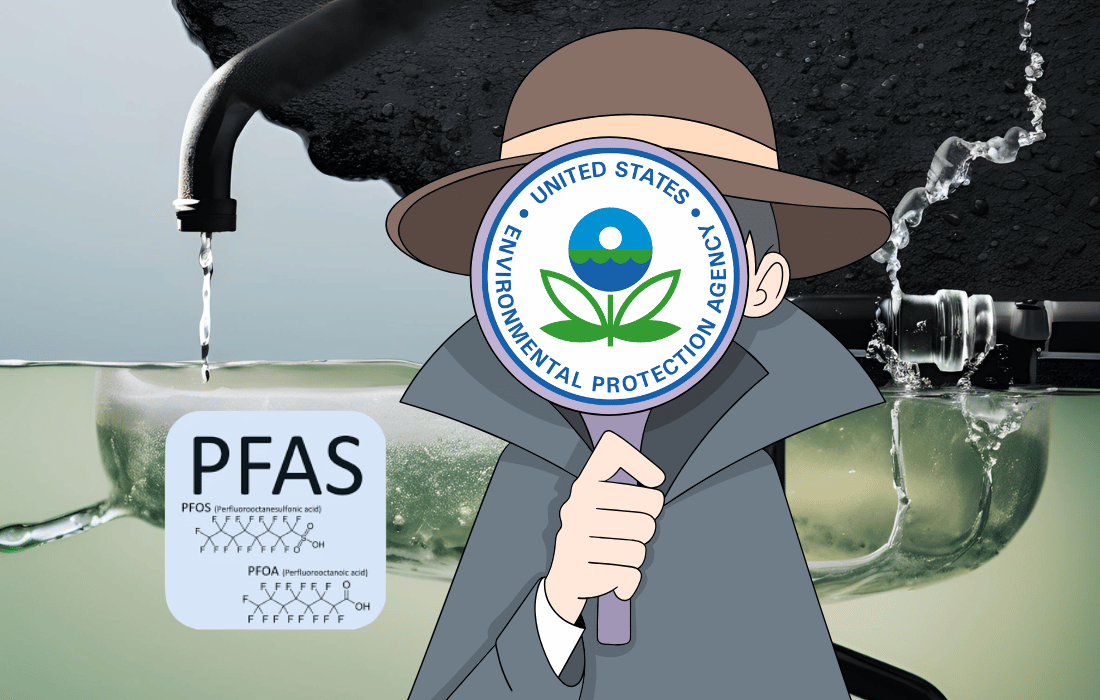

Let’s start with a not-so-fun fact: nearly half of U.S. tap water is now contaminated with PFAS—those pesky “forever chemicals” that just don’t know when to quit. They show up in your blood, in raincoats, in non-stick pans, in your drinking water. And thanks to a new shift in tone from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under Administrator Lee Zeldin, a lot of people—including former EPA insiders and public health advocates—are asking a hard question:

Is the EPA stepping up to fight PFAS, or quietly backing down to protect industry and water utilities from the costs of cleanup?

Understanding PFAS: What Are We Dealing With?

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are synthetic chemicals developed in the 20th century for their unique ability to resist heat, oil, water, and friction. They’ve been used in everything from non-stick cookware and stain-resistant carpets to firefighting foam and fast food wrappers.

The problem? They don’t break down. These chemicals can persist in the environment and the human body for decades. And now, 97% of Americans have detectable levels of PFAS in their blood.

Why Are PFAS Dangerous?

Health risks linked to PFAS exposure include:

Various cancers (kidney, testicular, prostate, etc.)

The EPA acknowledges these risks. But acknowledging risk and enforcing regulation are two very different things.

Major Sources of PFAS

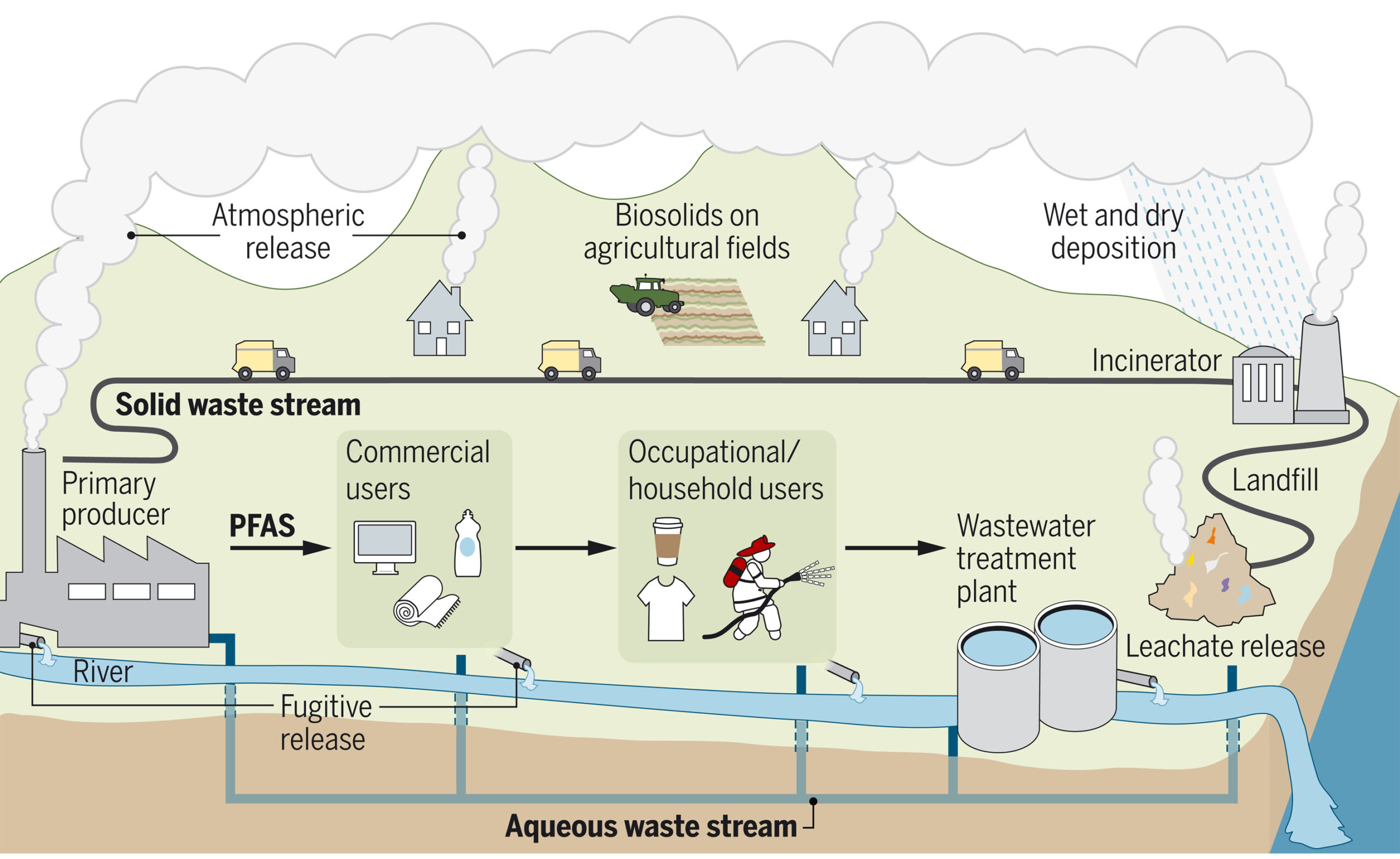

PFAS contamination comes from a wide range of sources. Some are obvious; others, less so. Here are the primary contributors:

Industrial discharges: PFAS are heavily used in the manufacturing of Teflon, semiconductors, textiles, and electronics. Wastewater from these industries often contains high PFAS concentrations.

Firefighting foam (AFFF): Commonly used on military bases and airports, aqueous film-forming foam is a notorious source of PFAS contamination in groundwater.

Food packaging: Grease-resistant wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, and fast-food containers often contain PFAS.

Household products: Non-stick cookware, stain-resistant furniture, waterproof clothing, cleaning sprays, and dishwasher gels frequently contain PFAS.

Personal care products: Lotions, sunscreens, toothpaste, and mouthwash may include PFAS for water-resistance or shelf stability.

Synthetic fragrances and cosmetics: PFAS are sometimes added to enhance texture, spreadability, or wear time.

Clothing and textiles: Especially water- and stain-repellent outdoor gear, uniforms, and upholstery.

Pesticides: Some pesticide formulations include PFAS-based surfactants.

Canned food: PFAS can leach from the inner lining of cans into the food itself.

Processed foods: Items wrapped in grease-proof packaging often test high in PFAS residues.

Infant formula: Packaging materials and processing equipment may leach PFAS into powdered or liquid formula, an issue highlighted by “Operation Stork Speed”.

Smartwatches and wearables: Certain fluorinated compounds used in waterproofing and heat resistance have been implicated in lawsuits, such as recent claims against Apple.

Landfills and biosolids: PFAS-laden items that get thrown away can leach into surrounding soil and water. Biosolids from wastewater treatment plants used as fertilizer also spread PFAS into agricultural soil.

Airborne particles and VOCs: PFAS can enter the air during manufacturing or from treated consumer goods and settle into household dust.

Knowing these sources helps us better understand how PFAS end up in our water, food, and even the air we breathe.

The Trump Administration’s New PFAS Strategy: A Step Forward or a Step Back?

In April 2025, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin unveiled what appeared to be a sweeping plan to tackle PFAS contamination. The announcement included everything from enhancing scientific research to strengthening enforcement tools. On the surface, it sounds promising.

But beneath the surface, many are seeing red flags.

A Shift Away from the Biden-Era Roadmap

Under the Biden administration, the EPA released the PFAS Strategic Roadmap in 2021. It committed to:

Designating PFAS as hazardous substances under Superfund law

Setting maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for PFAS in drinking water (as low as 4 ppt for PFOA and PFOS)

Requiring reporting and testing from companies manufacturing or importing PFAS

The Trump administration now appears to be walking back some of these commitments. EPA insiders suggest Zeldin may seek to extend compliance deadlines or ease the standards so fewer facilities are forced to act.

Reading Between the Lines: What the New Plan Signals

The EPA’s latest PFAS announcement might sound strong on the surface, but the real story is tucked into its phrasing. When you dig deeper, the language reveals subtle shifts that could prioritize cost-saving over public health protection.

Industry-Friendly Language

One of the biggest concerns is the administration’s language about addressing “compliance challenges“.

This could mean water utilities get more time before they must meet strict standards.

Or worse, it could mean loosening the standards entirely.

Zeldin’s EPA also mentions not “overburdening” small businesses and importers under the Toxic Substances Control Act. Advocates worry this opens the door to more exemptions and less transparency.

Delaying Tactics Disguised as Research?

The new plan highlights the need to “strengthen the science” and launch more testing initiatives. But many experts say this sounds suspiciously like a stall.

Dana Sargent, executive director of Cape Fear River Watch, put it bluntly: “If you’re claiming that you need more research on PFAS while you’re defunding research on PFAS, you’re being dangerous.”

Linda Birnbaum, former head of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, agreed. The devil, she says, is in the details—and those details are disturbingly vague.

The Cost of Cleanup: Who Should Pay?

Cleaning up PFAS from drinking water isn’t cheap. The American Water Works Association (AWWA) estimates annual costs exceeding $3.8 billion. Understandably, many water utilities don’t want to foot that bill, especially when they didn’t produce the PFAS in the first place.

Zeldin’s plan highlights a desire to protect “passive receivers” like water utilities. But critics warn this protection could come at a steep cost to public health if it leads to weaker standards or delayed enforcement.

Superfund Law Rollbacks

The Trump administration has also signaled it may repeal the designation of PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under Superfund law. This change would limit the ability of regulators to hold polluters financially accountable for cleanup.

Environmental attorneys warn that such a move would shift the burden away from the chemical manufacturers and onto taxpayers or municipalities.

What’s Missing from the EPA’s Plan?

While the EPA’s announcement is packed with high-level language and buzzwords, it’s what they didn’t say that’s raising eyebrows. Key elements that were previously central to PFAS regulation have either been dropped or left ambiguous in the new roadmap.?

1. No Mention of Landfills

PFAS don’t just end up in water. They leach from landfills into groundwater, or evaporate into the air. The new EPA plan fails to mention setting limits for PFAS in landfills—a glaring omission, given how significant this exposure pathway can be.

2. No Timeline, No Leadership

The announcement does not include timelines or the name of the agency lead overseeing PFAS efforts. For an issue as urgent as this, the lack of accountability is troubling.

Public Response and Rising Skepticism

Groups like the Environmental Working Group and Clean Cape Fear are already ringing the alarm bells.

Emily Donovan of Clean Cape Fear called the protection of passive receivers “a slippery slope.”

Melanie Benesh of EWG fears that the language used opens the door to exemptions for polluters.

The sentiment across the board? This plan could very well be more about optics than action.

AWWA’s Balancing Act

Interestingly, the American Water Works Association supports national drinking water standards but remains concerned about the financial burden. In its statement, AWWA called for source water protection and policy frameworks that keep PFAS out of the environment in the first place.

Their stance is clear: protect consumers and safeguard utilities bearing the brunt of decades of industrial pollution.

Final Thoughts: Public Health Should Come First

PFAS contamination is not a theoretical issue. It’s not a future problem. It’s here. It’s now. And it’s inside us.

The EPA has a responsibility to act quickly, transparently, and with integrity. That means setting clear limits, enforcing accountability, and investing in both research and regulation.

If the Trump administration’s EPA chooses to slow-walk these efforts or ease burdens on industry while communities continue to drink, breathe, and bathe in PFAS, then yes—we should be very concerned.

Health comes before politics. At least it should.